Green Roofs: A Primer

There is a new landscape emerging in North America, still largely unseen but gaining in popularity. That landscape is the green roof. Green roofs have started sprouting in urban areas everywhere, giving some of our favorite hardy succulents new opportunities to shine. Sedums and ice plants are the stars of many green roofs: Tolerant of heat, sun, wind, drought, salt, disease, and insects, these low-growing, shallow-rooted workhorses of the perennial plant world have what it takes to thrive in the tough conditions high atop multistory buildings.

One form of roof garden has been a popular design element for public spaces like parking garages and museums in North America for the last 50 years. In the lexicon of green roofs it's known as the intensive green roof. These roofs are constructed with a layer of growing medium most often measured in feet, not inches, and have elaborate irrigation systems as well as substantial maintenance budgets. Intensive green roofs have the look and feel of traditional gardens despite their higher elevation.

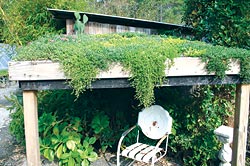

More recently, a second type of roof garden has come into existence, one that has the potential to benefit the environment in addition to soothing the eye. The extensive green roof is typically created with three to six inches of growing medium, has no irrigation system, has a very limited or no maintenance budget, and generally serves a practical, rather than mostly aesthetic, purpose. All year long, the extensive green roof soaks up stormwater that would otherwise run off, taxing city sewer systems and damaging receiving waterways. Extensive green roofs also help lower ambient temperatures during the summer months, lowering cooling costs and helping to mitigate the so-called urban heat island effect.

Many European countries, most notably Germany and Switzerland, have embraced extensive green roof designs for practical, environmental, and aesthetic purposes. As the boundaries of growing cities rush to merge with the countryside, constructing green roofs has become an important way to reduce the impact of ever-increasing impervious surfaces. By virtue of their planted areas, extensive roofs green and cool cities, increase oxygen output, soften urban streetscapes, and reduce stormwater runoff to vital tributaries and major bodies of water that supply drinking water to millions of people across Europe. So serious are northern European concerns about the environmental impacts of development that federal laws mandate that development must be offset by green spaces; as a result, 14 percent of Germany's flat roofs now sport green roofs.

North America lags far behind Europe in this regard. Urban jurisdictions are still coming to grips with major stormwater-management issues that are directly linked to the rapid spread of roads, pavement, and other impervious surfaces over the last 30 years. This, in turn, has left aging water and sewer systems prone to regular flooding, which has a serious impact on the quality of water in our rivers and streams. Because of this, there is tremendous pressure from both government regulators and citizen environmental advocates to address issues of stormwater management in a meaningful way. But how do you help cities that have been designed to shed water as rapidly as possible become capable of absorbing rainwater? Green roofs are the obvious answer. Studies conducted on green roofs over a three-year period by Bill Hunt and others at North Carolina State University, in Raleigh, have shown annual rainfall retention on an extensive green roof with a four-inch-deep growing medium to be around 60 percent. In addition to reducing the amount of stormwater runoff and lowering the summertime air temperature around buildings, green roofs also clean particulate matter out of the air, mitigate acid rain, extend the life of roof membranes by protecting them from harmful rays that are the primary cause of degradation, and perform many other site-specific functions, depending on design and region.

In England, for example, urban green roofs are being used to provide habitat for insects and nesting areas for birds like the black redstart, which have lost substantial habitat to development. Other buildings feature green roofs to boost worker productivity in offices—studies have shown that worker absenteeism is lower in buildings that are environmentally friendly, for example. Best of all, these benefits occur simultaneously, and collectively they give building owners a return on their investment of installing the extra layers that make up the green roof. As the measurable benefits are being quantified, public officials in the U.S. and Canada are beginning to embrace green roofs as an important tool in improving the quality of life in urban areas. One by one, local jurisdictions are giving incentives such as tax breaks to encourage green roofs and reduce the adverse effects of development. Look for many more green roofs to come.

Green Roof Basics

Deciding whether to plant a green roof should begin with a series of questions designed to pinpoint its primary function. Is the green roof purely aesthetic in nature, offering a green respite in a sea of asphalt? Is it intended to deal with stormwater runoff, in which case aesthetics might be a secondary consideration to water retention? Is the roof designed to have a therapeutic effect, say, as an installation atop a hospital, where patients might visit? Is it largely educational in nature, open to the public and serving to teach people about the benefits that green roofs offer? Determining the purpose of the green roof will help to determine a number of things, among them the most suitable plants, whether or not you'll need an irrigation system, and how much load the roof must bear and whether it needs to be retrofitted to accommodate the extra weight of the medium and the plants.

An extensive green roof with a planting medium between two and six inches in depth adds between 14 and 35 pounds per square foot. This is a substantial increase of weight, and a structural engineer should be consulted to make sure that an existing roof can accommodate the extra weight, or if not, how it can be retrofitted to do so. In the case of new construction, load bearing should be factored in at the design phase and worked out between architect and engineer. An engineer can also calculate other additional loads associated with a green roof, including live load, which factors in human foot traffic, temporary installations of furniture, and so on. Your architect or contractor should be aware of any special requirements in your area, including whether a building permit is needed to construct a green roof and whether there are any tax or other incentives for doing so.

Once you've determined the purpose of your roof and structural issues, you will need to find a reputable and experienced company that has worked on green roofs previously and is familiar with the necessary layers that each green roof requires. Briefly, those components include decking, waterproofing, insulation, drainage, filter cloth, medium, and, finally, plants. There are complete green roof systems available (mostly from German companies that have entered the North American market), or the green roof can be built layer by layer by a roofing contractor. Plan your roof for a minimum 30-year life span—it's costly and impractical to need to rip up the garden because of a failing in the roofing materials. (For more information on the structural elements of installing a green roof, see Planting Green Roofs and Living Walls, Nigel Dunett and Nöel Kingsbury, Timber Press, 2004.)

When it's finally time to start thinking about plants, you need to decide how much time and money to allocate for maintenance. Grasses, for example, must be cut back periodically to avoid becoming a fire hazard. Some plants need regular pruning, watering, or fertilization. You will also need to know how and when you will access the roof. If access is limited or there is no one to perform the maintenance needed for some plants, then you'll want to choose plants with minimal requirements.

Rooftop Environments

Rooftop growing conditions are usually much harsher than those found on the ground in the same area. For example, winds are much fiercer 20 stories above ground than they are at street level; they can quickly desiccate the plants and growing medium. To pick the right plants for the job, get to know the microclimate of your rooftop environment. As a first step, determine the minimum and maximum roof temperatures and observe how sunlight travels across the roof, noting if any sections are shaded by trees or other buildings for part or all of the day. Knowing the relative amounts of sun and shade the roof receives will help you pick plants that are most compatible with particular areas.

In general, green-roof plants should be ecologically compatible, fast growing but not invasive, and fire resistant. To avoid interfering with the well-being of the roof, they should also be long-lived or self-propagating, have shallow, fibrous root systems, and be lightweight when fully grown. As a rule, hardy succulent groundcovers are excellent candidates for green roofs, and of those, Sedum is the most versatile and common genus used. Sedums (also known as stonecrops) thrive in dry conditions and nutrient-poor soils, require little to no maintenance, and resist being blown over by wind because of their short stature. Many low-growing species and cultivars are available, and together with evergreen plants they can be arranged into interesting patterns that provide aesthetically pleasing roofscapes year-round.

Although it is not generally the case, in some circumstances, it may be desirable or necessary to irrigate an extensive green roof. It's doubtful, for example, that a green roof could survive in the arid Southwest without some kind of installed irrigation system for the hottest and driest months. Similarly, if you wanted to mix more demanding plants such as herbaceous perennials with the dominant succulents and grasses, it might be necessary to irrigate the roof (and increase the depth of the medium) to allow the less drought-tolerant species to flourish. Irrigating a green roof greatly expands the plant choices available to you, but it also increases the weight of the roof, the cost, and the need for maintenance. A variety of systems is available and should be thoroughly researched or discussed with a knowledgeable expert.

To help choose plants that meet your site's needs, it's best to consult a professional horticulturist, landscape architect, or local nursery business familiar with selecting plants for green roofs in your area. The vast majority of plants found on extensive green roofs are hardy succulents, including Delosperma, Jovibarba, Sempervivum, and, as noted above, Sedum. With more than 600 species of Sedum alone, the choices are extensive and varied and can offer a prolonged period of bloom.

Rooftop Aesthetics

Green roofs can easily provide visual interest throughout the year, even in areas with very cold winters. The roofs are not evergreen in the strict sense of the word, but they do offer interest year-round. For example, Sedum album 'Murale' illustrates the versatility of the genus in a successful roof design. As this plant breaks dormancy in spring, it turns into a lush green carpet, increasing in vigor and growing out horizontally over time. Come early summer, terminal flower buds appear, obscuring the foliage under a haze of white flowers for about two weeks. Later on, the spent flower stalks continue to contribute visual interest, or they can be removed if desired. When fall approaches, the foliage slowly turns red, progressively darkening until it reaches a burgundy shade. It stays that way until it breaks dormancy the following spring.

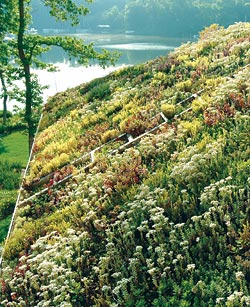

Living roofs provide many options for playing with multiple permutations of colors and patterns. The key to creating a successful roof design is remembering that it needs to please from afar. Large broad-brush splashes of color stand out well at considerable distance, while small, intricate plant details get lost completely. The bright red foliage of Sedum spurium 'Fuldaglut', for example, is a knockout from a distance, while the intricate details of the highly unusual gray foliage of Orostachys boehmeri can be appreciated only up close. (For low-growing sedums and other plants that offer superb foliage and flower colors, see "Great Succulents for Green Roofs" below.) Once you've selected low-growing sedums, you can add height, different textures, and colors to round out the design. Taller sedums like Sedum sieboldii or S. 'Matrona' work well, as do certain accent plants like Dianthus and Phemeranthus (syn. Talinum), which offer bright bursts of color when interspersed among other plants. Various ornamental onions (Allium) and short grasses like grama grass (Bouteloua) and sedges (Carex) can also be wonderful counterpoints to the hardy succulents that dominate the roof. Often, accent plants are not reliable enough to be dominant species, but if used wisely, they can add valuable interest to your green roof.

Depending on weather conditions, seasonal changes, and differences in climate from year to year, some plants will flourish, while others will recede. Some plants like Allium and Phemeranthus will self-seed from one year to the next, changing the garden's design. Over time, the unique landscape of your green roof will continue to evolve and change, even as it performs valuable services to your surroundings. With careful planning and a clever combination of groundcovers and accents, green roofs truly can provide a bright spot virtually year-round.

Great Succulents for Green Roofs

Combining fabulous foliage colors in broad sweeping patterns lies at the heart of an aesthetically successful green roof design, which will be viewed mostly from a considerable distance. Low-growing sedums and other closely related succulents offer a great palette to choose from: Their foliage comes in grays, blues, greens, reds, and yellows, as well as variegated forms, with many species and cultivars adding splashes of seasonal flowers and changing foliage hues as the seasons progress.

Sedums for Year-Round Interest

While not truly evergreen, these plants do not disappear in winter; rather, they assume winter colors from dark russet to brighter shades of red. During the growing season they form dense mats of green that are obscured only when they come into flower.

- Sedum album and cultivars

- Sedum hybridum 'Immergrünchen'

- Sedum kamtschaticum 'Weihenstephaner Gold'

- Sedum lanceolatum

- Sedum sexangulare

- Sedum sichotense

- Sedum spurium 'Fuldaglut'

- Sedum stefco

- Sedum stenopetalum

Sedums With Blue Foliage

- Sedum cauticola 'Lidakense'

- Sedum hispanicum

- Sedum ochroleucum

- Sedum rupestre

Ever-Blooming Succulents

Some perennials act like annuals when it comes to blooming: Once they start—typically in late spring or early summer in most areas—they bloom continuously until frost or, in subtropical areas, year-round. South African ice plants (Delosperma) and North American Phemeranthus (syn. Talinum) species, native to serpentine prairie ecosystems, make first-rate perpetual bloomers.

- Delosperma aberdeenense 'Abbey White'—white flowers

- Delosperma brunnthaleri—yellow flowers

- Delosperma cooperi—purple flowers

- Delosperma floribundum 'Starburst'—purple flowers with white centers

- Delosperma herbeum—white flowers

- Delosperma ecklonis var. latifolia—purple flowers

- Phemeranthus calycinus—purple flowers

- Phemeranthus rugospermus—pink flowers

This article orginally appeared in BBG's 2006 handbook, Crazy About Cacti and Succlents.