Lofty Liatris—Drought-Tolerant Beauties for the Summer and Fall Border

Most of us know Liatris via the cut-flower industry. It is yet another North American wildflower that Europeans have selected, hybridized, grown in large scale, and exported back to us for mass consumption. Long, purple floral spikes of Liatris can be found in everything from high-end arrangements to basic supermarket bouquets.

The good news for gardeners is that Liatris is much more than a cut-flower-industry standard. It is, in fact, a group of wonderfully diverse and easy-to-grow perennials that can brighten up the outside of your home just as beautifully as they can the inside.

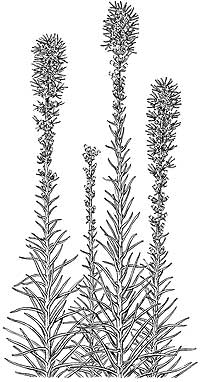

The genus Liatris belongs to the Asteraceae, or aster family, and is composed of around 40 different species. Common names include gayfeather and blazing star. Most of the species are prairie or grassland natives and have stiff, erect, two- to five-foot stems and grasslike leaves. The flowers (technically "flower heads" composed of multiple florets, or tiny flowers) are generally wispy purple, sometimes white, and they cover the top third of the stems in dense clusters from early summer to late fall, depending on the species.

One of the reasons gayfeathers are such popular cut flowers is their unusual mode of blooming. Unlike most plants with a similar inflorescence, they bloom from the top of their flower spikes downward. You can actually cut a good portion off the top of the spike (again about a third) to bring indoors, and the remaining flower heads will continue to open and add color to the garden.

Because of their vertical nature, Liatris species take up minimal space and are suitable for even the smallest garden. They are equally at home in large, established perennial borders, where their thin, tall, airy floral wands create a mesmerizing "pop-up" effect.

Besides getting a visual boost, your garden will also hum delightfully from the various insect pollinators that come to feed on Liatris flowers. Butterflies are particularly attracted to the nectar-rich blossoms. Birds will also pay a visit as they relish the fall-ripening seeds.

Drought tolerance is an especially desirable trait that Liatris species offer. Their water-retentive corms allow them to persist in lean, dry times. And cultivation is very straightforward. Most gayfeathers prefer full sun and well-drained soil of moderate to lean fertility. The majority of the species listed below are hardy from USDA Zones 5 to 9. I have never encountered any insect or disease problems. In fact, I can't think of a reason not to grow these plants!

Kim's Picks

Only one Liatris species (L. spicata, or dense blazing star) is readily found in garden centers. Why others tend to get overlooked is a mystery to me, as many are very garden-worthy. Thankfully you can usually find these species at specialty mail-order nurseries (see "Nursery Sources") or at local botanical gardens.

Liatris aspera (rough gayfeather) grows three to five feet high and bears lovely lavender flowers in late summer and early autumn. Because of its height, place the plant where it can lean into a shrub. The species is native to most eastern, midwestern, and southern states.

Liatris elegans (pinkscale blazing star) produces large, showy lilac-purple bristle-brush flowers with soft white inner petals from late summer to fall. It grows two to four feet high and is native from South Carolina to Florida west to Oklahoma and Texas. Note that it has a pretty narrow hardiness range, from Zones 7 to 9.

Liatris graminifolia (grass-leafed blazing star) is a very compact, one- to two-foot-high plant with soft, two-inch-long, needlelike foliage on reddish-pink stems. It produces a profusion of small, soft lavender to near white flowers in early fall. The plant's natural range is from New Jersey south to Alabama.

The large purple flower heads on Liatris ligulistylis (meadow blazing star) are a knockout! As many as 70 blossoms grace the three- to four-foot stems of this species in late summer. It can tolerate slightly damp soils in addition to well-drained ones. And it's indigenous from Wisconsin south to Colorado and New Mexico.

Liatris microcephala (dwarf gayfeather) sends up several one- to two-foot rosy-purple flower spikes from its compact, grassy rosette in midsummer. Because of its diminutive size, it is a great choice for planting among boulders in a sunny rock garden or as an edging in a sunny border. Rare in cultivation, this species occurs naturally in the southern Appalachian Mountains.

Liatris spicata (dense blazing star) sends up three- to four-foot lavender spikes in midsummer. This is another species that can tolerate moist soils. Numerous cultivars are available, including 'Blue Bird', with blue-purple flower heads, and 'Snow Queen', with white flower heads. It's native to many eastern and southern states.

Liatris squarrosa (Earl's blazing star) offers large, tuftlike red-violet flowers on one- to two-foot stems from early to late summer. Whereas most Liatris flower heads blend together, the blossoms on this species are individually distinct, making it a great choice for flower arrangements. It grows wild from Virginia west to Colorado and south to Florida and Texas.

Liatris squarrulosa (southern blazing star) produces bright, rosy-purple, inch-long flower heads on six-foot stems from late summer into fall. It was selected as the 1998 North Carolina Wildflower of the Year by the North Carolina Botanical Gardens. It's tough as nails, thriving in poor soils, and is native to many midwestern and southern states.

Plant Propagation

If you're not sure at first which gayfeathers to grow or how many you should buy, start off small and increase your numbers by propagation. There's nothing to it. Liatris seeds ripen in late summer to early fall, when they can be collected and sown directly outdoors.

The seeds need to be exposed to cool and moist conditions in order to germinate the following spring. To keep track of your plants, collect seeds when they ripen in the garden and sow them in flats. Leave the flats outdoors over the winter, and germination will occur when temperatures and soils begin to warm up.

If you have the patience and the facilities, you can accelerate this process by bringing the seeds indoors after two months of winter temperatures and sowing them in a warm greenhouse. Germination will begin within two to three weeks. Pot up seedlings into three-inch or quart containers and plant them outside after the last frost date in your area.

You can also mix the seeds with slightly moistened sand in a plastic bag and place them in the refrigerator directly after harvesting. Remove after two months and sow them in germination flats in a warm greenhouse. The seeds will germinate quickly. Again, pot up the seedlings and sow them outside after the last frost.

On older plants, the tuberous corms can be dug and divided during late winter while dormant. Softwood cuttings can also be taken in spring. However, propagation from seed is the easiest and most reliable method.

Designing With Liatris

Plant several Liatris species in your garden to ensure a full season of summer and fall blooms. The purple tones of their flowers will complement the flower colors of almost any other plant. Combine Liatris with deep-blood-red daylily cultivars such as Hemerocallis 'Anzac' or 'Ed Murray', for instance, for a rich, saturated, attention-grabbing duet.

In a casual cottage garden, Liatris species mingle easily with other summer favorites like Rudbeckia and Echinacea species (coneflower), Boltonia asteroides, and Asclepias tuberosa (butterfly weed). For those of you with meadow gardens, this plant of the prairie is a natural.

Gayfeathers provide indispensable vertical pizzazz to the mixed border. My favorite design strategy is to mix them with plants of similar hue. Verbena canadensis 'Homestead' combined with Allium sphaerocephalon (drumstick allium) and Liatris make for a stunning purple trio of varied textures.

This monochromatic scheme easily stands alone, or it can be embellished by adding Pennisetum setaceum 'Rubrum' and Canna x 'Bengal Tiger' (with its bold green and yellow vertically striped leaves) to the rear, and by planting a sweep of Echinacea purpurea 'Kim's Knee High' (compact purple coneflower) in front.

A simpler combination features two North American natives: Rudbeckia fulgida 'Goldsturm' (black-eyed susan) and Aster oblongifolius 'Fanny's Aster'. The round, bright-gold blossoms of the horizontally spreading black-eyed susan contrast wonderfully with the vertical purple spikes of Liatris spicata. Mix 'Fanny's Aster', Solidago rugosa 'Fireworks' (goldenrod), Chrysanthemum x 'Single Apricot Korean' (apricot daisy), and Liatris squarrulosa for a glorious grand finale in the fall border.

Liatris is a versatile North American genus with lots of ornamental appeal. Its ease of culture, durability, and long season of bloom make it a must for beginner and experienced gardeners alike. Tuck it here and there it in your garden this year and you'll be nicely rewarded. Kim Hawks is the owner of Niche Gardens, a nursery in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, specializing in nursery-propagated wildflowers, selected garden perennials, ornamental grasses, and underused trees and shrubs.

Nursery Sources:

Niche Gardens1111 Dawson Road

Chapel Hill, NC 27516

919-967-0078

www.nichegardens.com Prairie Moon Nursery

Route 3, Box 1633

Winona, MN 55987-9515

507-452-1362

www.prairiemoon.com We-Du Nurseries

Route 5, Box 724

Marion, NC 28752

828-738-8300

Prairie Nursery

P.O. Box 306

Westfield, WI 53964

800-476-9453

www.prairienursery.com