Pondlife: What Lives in the Water Here?

Our world is microbial. In every drop of water and handful of soil there are thousands of microbes, living out their lives and making ours possible. They produce our oxygen and degrade our waste. They provide plants with critical nutrients and help us digest our food.

The term microbe means any living thing that is too small to be seen with the naked eye. Bacteria are microbes, but so are many other types of organisms. Protists, algae, and archaea are all microbes. In fact, there are more species of microbes than there are species of plants, animals and fungi combined.

A few weeks ago I visited Brooklyn Botanic Garden to examine the microbial menagerie in some of the water features. The Garden has several freshwater ponds, and each has its own characteristics. The lily pools, for instance, get sun all day and are lined with concrete. The plants grow in submerged pots filled with soil. The newest pond in the Water Garden has an earth bottom with a deep layer of soft mud and silt. The water here is filtered by a bank of sand and rocks as it flows in from a brook. I took samples from both.

Lily Pools

My first stop was one of the pools on Lily Pool Terrace, where the water was looking decidedly green. I always get excited by green water. Green indicates an overgrowth of algae. These kinds of blooms can sometimes be harmful, producing toxins or sapping the pond of nutrients. But in general, these overgrowths are part of the normal seasonal cycles of the pond. Freshwater species of microbes, particularly algae, tend to bloom over the summer due to the warm temperatures and many hours of sunlight. And when that happens, other microbial species can bloom too, making their homes on and around the algae.

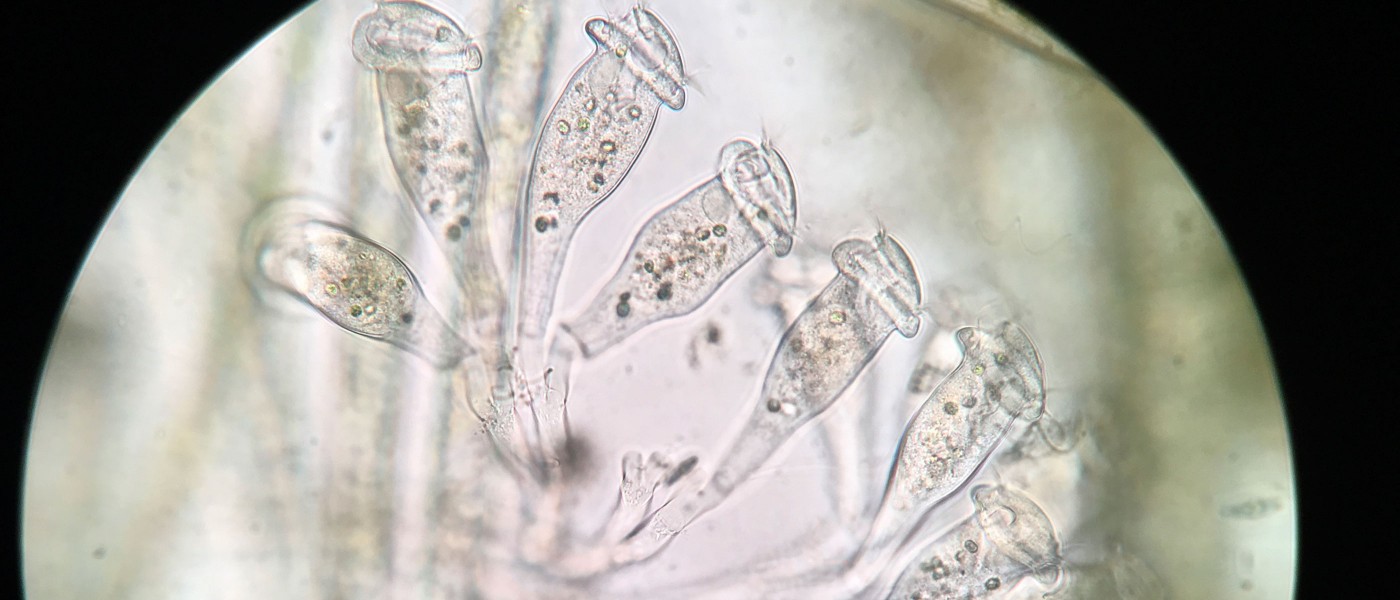

The first species I filmed from the lily pool was a colony of Epistylis ciliates. Ciliates are a type of unicellular protist. Epistylis is a genus of bell-shaped cells that grow in colonies. Each cell sits atop a fine stalk, which anchors it in place. This colony is anchored to a green alga that I collected near the edge of the pool. An Epistylis cell is a hunter. Its top has a ring of hairlike structures called cilia (ciliates always have cilia—that’s how they get their name).

The cilia surround the mouth of the cell and beat back and forth to create a current in the water. That current draws in cells that happen to pass by. Each Epistylis cell here contains green dots. Those green dots are cells of the some of the same algae that give the lily pools their green color. These algal cells have been consumed by the Epistylis. If you watch carefully, about halfway through the clip, the second cell in from the left catches a passing green algal cell and swallows it. Yum.

This second clip is of a rotifer from the Collotheca genus, another common pond resident living among the algae. Rotifers are microscopic animals made up of several hundred cells. They have tiny mouths and stomachs and even some neurons. This particular rotifer is carrying eggs—those two oval lumps near its base. Rotifers stay attached to their eggs until they mature. They are doting parents indeed. Like the ciliate above, this rotifer also lives by eating algae. It has long sticky tentacles that extend from its top end, surrounding its mouth. The rotifer uses these tentacles like a fishing net, waiting for morsels of food to swim in and become entangled.

Water Garden

Over in the Water Garden pond, things are a little different. The water itself is clear and for the most part free of algae. Perhaps bloom species of algae haven’t colonized this pond yet, or perhaps the pond’s filtration system keeps them out. Unlike the lily pools, this pond has a mud bottom.

As I walked up to the pond’s edge to take a close look, I also noticed that the muddy bottom was coated in a thin layer of air bubbles. Algae living in the muddy bottom will produce oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. This oxygen accumulates into small bubbles, kept in place by water tension. Bubbles on the surface of the mud indicate microbes living within. I scooped up some of the mud from the pond to take a look at the microscopic bubble blowers.

Soil and mud and silt are hotbeds of microbial life, although they tend to accumulate different species from those of the water above. Sure enough, the type of algae living in the mud are not green but golden brown. They are diatoms, which contain pigments that absorb different wavelengths of light than those of green algae. Not all wavelengths penetrate the surface of the water. The pigments in diatoms are better at absorbing those that can, so they can live at greater depths than the green algae.

The diatoms living here are in the genus Navicula, meaning boat shaped. And boat shaped they sure are. Each diatom cell sits within a shell made of glass called a frustule. The diatom builds its frustule by collecting silica from the environment and then excreting it around itself. They are beautiful organisms. Navicula frustules taper at each end, giving them their distinctive boat-hull shape. Navicula diatoms are also capable of movement, and the ones here are constantly on the go. They glide back and forth through the mud, moving in and out of sunlight and away from predators.

Just like green algae in the lily pools, the golden-brown diatoms in the Water Garden pond make a great meal for hungry microorganisms. Lurking in the mud is another type of ciliate, a cyrtophorian ciliate. These unicellular predators are also covered in cilia, just like Epistylis, but they use their cilia for movement and are not anchored in place like Epistylis. They forage through the mud, just like a badger in the forest undergrowth. On the bottom of the cell there is a mouth ready to scoop up any diatom that can’t get out of the way fast enough. These ciliates are already full of diatoms but are still looking for more. No wonder the diatoms are always on the move.