The 41st annual Making Brooklyn Bloom conference celebrates the Garden’s year-long focus on urban trees. By improving air quality and reducing stormwater runoff, giving us shade on sunny days, and providing wildlife habitat, trees play an undeniable role in mitigating climate change.

The day’s workshops, tours, and keynote address will inspire the equity, advocacy, and care needed to lead us into a more forested future. Visitors will have the opportunity to network with NYC greening organizations in the Palm House.

Arrive early—spots for workshops and the keynote address fill quickly. Garden admission is free for attendees. Walk ups also welcome! Note: Admission does not guarantee space in Making Brooklyn Bloom events. Keynote and workshop registration begins at 10 a.m. in the Palm House, first come, first served. You must be present to register. Email [email protected] by February 21, 2023 to request ASL interpretation. Visit bbg.org/accessibility for more information. “Can urban greening projects address historic injustices, respond to community aspirations, and draw on traditional ecological knowledge? The recent convergence of climate change, racial reckoning, and economic inequities have awakened many to a new era in which urban forests are seen as a central solution. Yet, we need a new framework to help us avoid the pitfalls of both communities without trees and trees without communities.” Watch Dr. Shandas' speech below: Dr. Vivek Shandas (00:00): Hello, everybody, it's a privilege to be here, I can't thank Sonal, Adrian, the Levin family, Jibreel, and all of the folks who were essential, instrumental, catalytic to enable this to happen after what, three, four years of hibernation, it felt like. So when we’re together like this, we're building relationships. We’re connecting. It’s great to be on little video boxes, I’ve seen many folks, as you have, on little video boxes. But to build relationships like this is really what I would like to talk about today. This is work that spans about two decades of my thinking on the topic of trees, of trying to recognize that we are connected to our leafy kin, and trying to really build a future that next generations, for time immemorial, can really learn from and engage with. (01:01) I come from a family that immigrated from eight degrees above the equator in South Asia, and my family pulled me from my friends and family when I was about ten years old and dropped me in Northern California, where I was so fortunate to find solace, and reparation from the transition, 10,000 miles, within the redwood forests. So those redwoods are in my heart today and really helped me come into a place of recognition that I need to give back to them. And I’d like to talk today a little bit about that relationship that I have to the trees, and of course, to our ecology. I’m going to start with a simple, deep history piece. (01:59) I wanted to find a way to really think through how we might actually present and position ourselves within the world of Brooklyn, within the world of nature, and within the world of the future. So part of what I’ve had the good fortune to do is travel around the world and look at cities. Part of the transition, coming from South Asia, and the transformation that I had to experience as an immigrant moving from one part of the world to another, was trying to reconcile how people organized landscapes. (02:55) When I was growing up, I would walk into my family house in an apartment that was next to some really big banyan trees and there would be monkeys that would jump off of those trees, come into the house, and start rummaging through the pantry. And as I walked home in second grade, finding my mom up against the wall with monkeys rifling through the pantry, was a moment of recognition that we organize space and allow things in different places in different ways. And it still works. I was still able to go to school, my folks were able to commute, it still worked. It was from many interpretations, a pretty chaotic space to live, with chickens and cows and monkeys and all kinds of insects that were the first experience that I had growing up. Moving, then, to northern California, to a suburban community where everything had its individual place, ended up creating an immediate question in my mind that I’m still trying to resolve today. How do we organize space in the places we live? What are the things that drive the priorities? And how do we actually find ways to reconcile the space that has already been spoken for from generations past? (04:18) So those are the questions that really drive my space. The pictures up here are really part of my own reckoning that a lot of the Indigenous communities, a lot of traditional communities, that are still alive and well and which in many ways my family is beholden to, were deeply connected to nature. The deep roots that I’ll talk about in a minute—a lot of the spiritual traditions, lot of the religions that emerge from that really came from a record recognition that we are deeply intertwined, connected, dependent upon our leafy kin. So that's the spirit, the passion, from which this work really emerges. (04:56) And this tree, this massive tree in the middle picture, he’s in his late 80s. And I took him to India to go spend some time with family during the cold and rainy West Coast weather. And I was walking around a city of Bangalore where I spent a lot of time in South Asia. And these massive trees, that middle tree, a banyan tree—I don’t know if you know banyans, but they send huge, essentially roots, air roots, down and those have all been kind of taken care of, but it’s allowed to be right in the middle of the sidewalk, just allowed. So the organization of space, a theme I’ll come back to and the one on the right is LA, artistic approach of people trying to render trees and trying to bring both the human and the ecological, as we are part of nature, together in an artistic expression. So these pieces will help build themes that go into deep history. (06:00) Before Brooklyn, before there was New York City, before Long Island, before the United States, there was a real moment of land plants that were about 500 million years old. So when humans arrived on the scene, scientists tell us about 200,000 years ago, land plants were the first things to give us our first breath. Right, we are breathing out carbon dioxide, plants give us oxygen. And we were, from the beginning, highly dependent on plants. And as a result, the Indigenous peoples—and in this case, we know the Lenape were here in this particular part of the planet—recognized that these plants and these seasons that change these plants, and the weather that changes the plants, were part of something that we need to be able to really reconcile and make sense of. (07:01) And so the Indigenous communities, one by one, all over the planet have really found ways to either rotate particular plants—in this case of New York, corn, beans, squash was an intercropping process that allowed not only selective use of fire for clearing lands, but also moving agricultural patches from place to place based on seasons. So this was something that was just inherent in the way that we think about and know about how Indigenous peoples live. And this is after the glaciers, right, glaciers, we’ve had about 10,000 years of stable climate on the planet, at least in this part of the world. And that 10,000 years, shortly after the glaciers receded and really created the over 1,000 hills in the New York City area, and hundreds of miles of stream. Those glaciers, as they receded, the Indigenous folks came right in. And they were very connected to the landscape and to whom we are in every way grateful in terms of understanding these processes. So this Indigenous knowledge is something that I really want to spend a lot of time trying to get a better understanding of with our conversation today. (08:17) That Indigenous process was quickly transformed when we started seeing many parts of the world wanting to explore the rest of the world. This is a process that’s now often called settler colonialism, which essentially has a set of attributes that, when European nations largely moved into North America, there was a recognition that there were particular systems that would either through repression or genocide, start erasing, segregating, and in many ways dispossessing land that was once harvested, that was once stewarded, that was once deeply cared for. And so those systems were attempts to not necessarily move across the land and find different ways of moving through the seasons. It was really to extract. And that’s a big part of settler colonialism is the idea of extractive economies. The land was no longer something that we depended upon for our survival. It was something to make money on through an economic system. (09:31) Right, so this is where we get into this idea of dividing up lands. This was a process that had been around for thousands of years, though became kind of hyper-activated once North America and once the process of dividing up communities based on ethnic or racial background became a part of the decision-making and value structure that we hold. This particular process took place in New York in a variety of different ways. And this example, was one of the most genius moments, in 2017, when a group out of the University of Richmond digitized, meaning took these old maps from the 1930s, which are some of our best evidence for this settler colonialism, where neighborhoods were divided up. (10:27) And for those of you familiar with Brooklyn, I put this up here as a way to show the original map from the 1930s that shows that specific neighborhoods were considered, quote, “best,” specific neighborhoods were considered “still desirable.” Other areas were considered “definitely declining.” And yet other areas were called “hazardous.” And this is coming out of the Great Depression, remember, in the 20s, coming into a time when we were trying to get the economy up. And unlike today, Congress and the president were working together really tightly, and it was just this moment of tremendous catalytic activity. And the federal government was able to pass a series of laws. One that was codified was this process of redlining. It was administered by two federal agencies, the Homeowners Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration. (11:28) Those two federal agencies worked with local land use planners in New York, in Oklahoma City, in Portland, in Miami, San Diego, 200-plus cities, to divide up cities into these four categories A, B, C, and D. And as a result of this particular process of segregating neighborhoods, we started seeing language showing up for how these neighborhoods were described. And here’s just a sample of what I picked up from Brooklyn. This is a way of describing specific neighborhoods and whether they were worthy of investment, and largely based on immigrant status, color of one’s skin, and in many ways, whether people are frugal or not. Right, really, this project that came out of Richmond was just a moment of transformation for folks like me, who are really interested in trying to understand, where do these disparities come from? And when we look at these kinds of maps, they start telling a story. (12:39) So what we did was we took these maps, essentially, and started to explore what it might mean to look at them in terms of modern-day interpretation of what's happening. So we took these and looked at 108 cities across the United States. And as we looked at 108 cities across the United States, we took these maps, and we just wanted to say, how much tree canopy was in these A, B, C, and D neighborhoods? In this case, this Homeowners Loan Corporation, it was a security map. And if you were living in an A neighborhood, you are likely to have more trees in your neighborhood than hard concrete surfaces. If you’re living in the opposite end, in the D neighborhood, you would have almost two to three times more. (13:33) These are averages across 108 cities—you’d have two to three times more concrete, asphalt, industrial facilities, freeways, right? All these land-hungry, large-scale infrastructure projects, looking for places to go, where land was cheap. And by design, these D-rated neighborhoods would have lower land rents. And as a result of lower land rent, if I want to put a freeway in, where do I go? A cost-benefit analysis would tell me I would go right to the lowest-cost place. Like when you’re thinking about buying something, think about that affordability of something, those freeways, similar logic. And so why do we have freeways next to Black neighborhoods? Why do we have industrial facilities next to a lot of immigrant neighborhoods? Why do we have Indigenous populations on reservations? All part of the same settler colonial process at work. (14:38) So this was arguably one of the first studies to scientifically provide evidence for the relationship between a policy that was enacted in the 1930s and banned in 1968, through the Fair Housing Act, yet was still creating a disparate, inequitable distribution of canopy, green space. That canopy then is highly connected to one of the biggest challenges that we’re confronting right now, and what Emily was describing earlier today—temperatures. Our planet as a whole is warming. And as our planet as a whole warms, cities are right in the epicenter. We build spaces, we have concrete, asphalt, buildings that retain that sun’s radiation, hold on to it because of these dense surfaces, and then re-emit it out. (15:38) So when we see particular heat waves coming through a region, those places that have less canopy, less green space, are on average 15 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than areas that had less canopy. And how do we trace that back to systemic processes of policies that were promulgated in the 1930s that are having an effect today? So this is where we are. This is from a colleague from the World Bank, who I’m so glad to see here today, Nick Jones, I brought this up partly for him. Thank you, Nick, for joining. This was a great way to describe all the different ways our cities are heating up the planet and for our experience in cities, in terms of what we are exposed to. As temperatures go up, the different forms we are presenting this and showing this work is very much linked to the hotter temperatures, and it’s very expensive. So this was a very, to me, coherent story that starts coming together. And this has been largely what our work is based on. (16:57) New York City is no stranger to heat. Some of the earliest heat work was done here. Heat vulnerability analyses and indices like this one are still continuing to be developed today, as you may have heard earlier, as well. And this distribution of heat is no coincidence, either. The physical experience of heat, combined with a community social coping ability, combined with the landscape that a community is surrounded by, are factors that coalesce and create greater or lesser vulnerability to these heat waves. As you heard earlier, more people die of heat waves than any other natural hazard. So trees and heat really start playing a very significant role. The New York Times came out with this piece last year, kind of really highlighting the tree inequities or the green space disparities. And this was really about the relationship between income and green space. Wealthier communities having more green space, lower-income communities—probably not news to most of you, in this world. (18:07) This was now something that’s much more mainstream and become something that has really taken off in terms of even why the feds have approved a $1.5 billion Inflation Reduction Act component that is about building canopy in places that have historically not had canopy. Recent findings, we looked at New York City and a bunch of other cities, and just to touch on this last piece of scientific investigation that our group has done, is we looked across New York City boroughs and said, we know that presence and absence is a thing, whether you have more trees, less trees. We were able to take it down to a step further and say that even the size of trees differs by neighborhood. (19:00) Income drives size of tree—if you excuse my clip art—number of trees, stems, density of trees, varies by income. Pretty easy. We can document this scientifically. Species of tree. And when we talk about a little tiny bug like the emerald ash borer that wiped out millions of trees in the Midwest, we’re really talking about species biodiversity, right? The diversity of the trees. So when you get one pest like an ash borer, a little insect wiping out an entire five, six states of trees, they largely planted ash trees. That’s why that diversity wasn’t there, and one bug went to town. So the species diversity is also tied in with this income question. So—right? Heavy. (20:01) This is where science is right now, this is where my world is. It’s about recognizing these things that have happened long before I was born, long before my parents immigrated to the U.S., long before—well, at least I know, not maybe 100% of you, but maybe all but one person, was likely alive. Right? This stuff was happening a long time ago. So what does this have to do with today? And where’s the work? Where’s the work right now? And that’s where I want to spend the last 15 minutes that I have here. (20:40) So the work as I see it is largely related to addressing trauma. This is societal trauma, trauma has been a word that’s now become very centered in terms of recovering from the pandemic impacts, trying to recognize that we have a lot of intergenerational trauma that has been part of our inheritance over time. And so where do trees come into this? I just want to offer a few words to begin this, because this, I'm not a social worker, but I really feel like one of the most instructive things that I’ve had is trees as teachers for addressing trauma. And that’s kind of where I want to go, because what do trees do? They bring, they gather inward, they kind of pull in when they’re hurt. (21:33) When you see a tree that’s been cut, it starts really pulling in—the sap may drip for a bit, it pulls in. Trees also express outward to the tips of their leaves, they stretch out, they’re really wide open, they start to bring in more of that sunlight into their leaves, into their needles. They rise up, right? They root deep. They tap—they go to search for connections. And in many ways, trees are also connecting and regrowing entire systems when they endure trauma. I was lucky enough to tour around the Brooklyn Botanic Garden a couple of days ago, just spent literally eight hours walking in the Garden. And it was one of the most uplifting moments of the last two weeks for me, and I recognize that even interpersonally, as you might as well. And so this reconnecting and regrowing whole systems is something I want to spend a little time with. (22:36) And so the ABCs that I’ve come to recognize in terms of trees and trauma really comes down to a few things that, again, is not necessarily new to you, but I want to try to, if I can offer anything, it’s the first acknowledgment of what we have—as a generation of people coming into cities, and with this climate change effect on us—what can we do, first and foremost? Well, we’re coming into this already a bit traumatized with the way the landscapes have been designed, decisions have been made, value systems have been inscribed. And from that, we want to think about, what would the trees do? We would acknowledge that, yes, a part of this trunk has been sliced, pull in, sap going inward, we want to activate the roots, branches and leaves. Now I want to get into examples of how we’re doing this in our work right now. We want to connect with others. (23:35) Trees have an enormous dendritic network, right. And when you talk about trauma, dendritic is a critical phrase because our nervous system has dendrites, just like a tree. And trauma affects our nervous system first and foremost. So this connecting is a way of being able to come together in relationship, and then to develop the priorities to say, Hey, this is something we really need to address. This is something we want to try to find a trauma-informed approach around. This bonsai in the bonsai collection here that I took a picture of a few years ago—phenomenal. The soil has been removed, yet the roots are going around it, it's ingesting, it’s bringing that rock into its own magnificence. It is bringing that trauma in. It’s not trying to isolate it, not trying to forget it, it incorporates it, it brings it in, it recognizes it, acknowledges it, it connects. (24:42) And so here’s where we’re going with this work. How do we operationalize this? Okay, fine, poetic, fine. We need to do the work. Where’s the work? And I wanted to start with this simple set of examples. The first example, acknowledgement. We have, we had this project in LA, where—I mean, massive concrete jungle, deep trauma, right? Lots of immigrant communities, lots of African-American communities, it was once part of Mexico, right? Like it was once part of Mexico, all of California. And then we’re now thinking about all these communities that are there that are trying to navigate and move through what it means to bring canopy back into a place that is pretty much concretized. Some places more than others. Almost 30% of all the tree canopy in LA is in four neighborhoods. (25:41) So these are the realities of what we’re trying to grow back and cultivate. And so we wrote these two reports, as some of this work, to first acknowledge what are we seeing in terms of the patterns of green space, these are urban forest equity reports that really try to bring that in front of the first urban forest officer that the mayor had appointed. So we wanted to put this right in front of her and say, This is the stuff we’re really trying to work with. We came up with a simple little graphic that talked about the investment and effort and the greening that a city could move forward. And different tiers. Tier one is where you could get a tree in the ground, it’s an open tree well, you can drop a tree down pretty easily in these spots, we created a prioritization matrix looking at different neighborhoods, historical trauma in those neighborhoods. (26:30) And trying to figure out where was a tier one, easy, drop a tree in, get green space, accelerated quickly. Tier two, a little more moderate, difficult to get trees in, you might have to really redesign a space. That’s where we are with this work. And then in tier three, very hard to do. This would be like a lot of Brooklyn streets, very hard to do. You have to really rethink—we’ve done it, bike lanes, there’s so much, since coming back to Brooklyn after a few years, there’s a lot more bike lanes, we can do this, right? This is the same question. Yeah, we can do this. Dense environments that I’ve traveled in, as I was showing, the first picture, have done this all over the world. We can do this. (27:19) A second example about becoming activated and really kind of reaching out is this project that’s been just taking off now. It's been so humbling and a privilege to be part of this process of heat mapping. We've been engaging communities all over the country and now world, in going out, taking little sensitive temperature and humidity sensors and going out and collecting tens of thousands of measurements. And part of this process has been allowing us to really get this information in front of folks. We might know that some areas are hotter than other areas through our lived experience. Yet when it comes down to actually documenting it and putting a map in front of a decision maker—changes a lot. (28:13) So what we’ve done is, we’ve, for example, here’s something in Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan that we worked on with a group with several community groups, including a group out of New York called WE ACT, who I think are involved in some of the Forest for All agenda here in Brooklyn. And were able to go out and collect tens of thousands of measurements. And using some pretty fancy math and mapping techniques, were able to say which areas are hotter than another. And on that one day where the high was about 95 degrees, we were seeing about a 10-degree difference. I’ve done this enough now to know that as temperatures go up, that difference widens. And so on a 95-degree day, it might be 10 degrees from one neighborhood to another on a 110-degree day, it might become 15 degrees, and on a 120-degree day—hope you don't experience it, I have, no fun. It might go even up to 20 degrees. (29:10) So this is now, lucky to work with a couple of federal agencies, they just said this checks all the boxes—we want to do this massively all over the country. And it’s just been phenomenal to see how many social, environmental justice organizations are working. We’ve got a whole cadre of people who’ve kind of been through this program and really working. And thanks to Nick and thanks to others, we’ve done this now in Indonesia, in Brazil, in Sierra Leone, and it’s really taking on a whole life of its own. Pretty fun stuff. Because the hard work begins once we go out and collect the data. That’s the easy part. This is the easy part. (29:51) We take the data in high resolution there, I mean, we can essentially, what we feel on our bodies, it's very high-resolution descriptions of air temperature. So we’re able to then take that and link it to a whole bunch of other data sets and put it in front of folks in terms of a very accessible interactive platform, where we’re seeing, hey, wow, this particular area, in this case, Tacoma, Washington, in February or in June, has a level of air pollutants and a level of heat that might be really harmful to a lot of communities who are experiencing asthma. What can trees, what can green space, how can we think about the services that these trees provide as a mitigative solution through these high-resolution descriptions of what we’re seeing in terms of exposure? Again, not that hard. This is like, stuff we do, relatively straightforward. Where it gets really a bit more complicated, is when we start bringing the stakeholders together, just like the trees kind of bring stakeholders together. (30:58) We want to start saying, What do you want this place to look like? If this is what it looks like today? What do you want this place to look like in 2050? So we’ve been doing these innovation plazas, these scenario-planning exercises by bringing diverse stakeholders together, essentially enabled to say, What is it that you would like Brooklyn to look like in 2050? And it’s an open question—planners have an approach to this, transportation engineers have an approach to this. Community-based organizations working on specific topics, social workers have a say in this. So we really create a big tent for the conversation. And that allows us to then bring the data and the conversations together in a future-casting exercise that allows us to say, Okay, if 2050, 2080, this is what you’d like this region to look like, how do we then start working systematically to reach that goal? What do we need to do by 2035? As in the 30 by 2025 approach? And then what do we need to do tomorrow? Wish we’d done it yesterday. (32:02) A bunch of other things that we’ve had—this was something that a group of residents came said, What if we were to just mow down all the trees in our neighborhood? Like, Wow, sorry, okay, fine. Let’s see what happens. So we pull these off-the-shelf fluid dynamics models, they’re computational models, computer-based models, that allow us to take a neighborhood or a city block much like this—the green is the trees, the orange is the open space, meaning the bare soil, the gray is the buildings, the black is the roads. We know the temperature there. We take all the trees out. Computer, tell us what would happen when you push a big plume of hot air through this particular city block. (32:54) And what we find in this case is that when you do that, temperatures go up by about 13 degrees Fahrenheit. Right, we don’t want to try this for real. Right. So what we’re trying to do is simulate this in a way that allows us to give a better understanding of what it might look like we did this for multifamily residential, working with this group of planners. And that allowed us to look at a whole bunch of different scenarios of configuring multifamily residential units. And we found that we could in fact, increase density from 16 units to 64 units on a city block, while—that’s what this graph is—while keeping temperatures below what they were with the 16-unit scenario. (33:45) All this stuff is starting to appear in heat management plans, which we’ve been now getting deeper and deeper into. This is gonna, this is something that falls through the cracks. The Department of Transportation, even Brooklyn Botanical Garden, no one entity is going to be able to own this, it often falls between the cracks. So we’re trying to fill in that space, because it’s really something that no one is owning right now. So how can we help in generating some of these planning efforts? Last thing that I will say is this project that we have going in Jackson, Mississippi, which is really bringing together all of these communities. (34:25) Working in climate change in Mississippi has, I don’t know what to say, not been easy. Nevertheless, it’s one of those places that has been historically segregated, dispossessed, and highly colonized by systems of oppression. And as a result, we’re trying to engage practitioners and residents on Fair Street, just one corridor, a historically African-American, Black neighborhood, which has two churches. So we’re working with faith-based organizations to start exploring, what does it mean to actually do this greening in real time, and how can we use the tools that we have access to, to bring information and so that you can start advocating for the greening of this neighborhood? (35:10) So with that, let me just close out, these are just a set of examples going from what we know to where we’re headed. And I want to just really underscore a couple of points. This is a playbook we’re developing together. This is something that we can really learn from, from our nature-based friends. And this is something that collectively is not insurmountable. And now’s the time where the feds have recognized this, community groups have recognized this, it’s the time to springboard into the kind of action that I think we all know what needs to be done. So these are a few examples to really get us started with that. And I hope to engage with you in a conversation about this work as well. Thank you. (36:08) So this is a work in progress. What do you think? Is this trending in the right direction? Are we hitting a moment of a rock where we need to grow around it? What comes up for you as you hear some of this, any thoughts? Questions? Reactions? Really curious, I’m fine if this is way off from what you're doing. This is giving you something to work with? Yeah, right over there. Audience member 1 (36:43): So I wanted to ask a question about one of the previous slides where it showed up crime rate and how, shows how crime rate and medical were related to increases in climate. I was wondering if you could elaborate on that a bit more. Dr. Vivek Shandas (37:01): Yeah, so this is work that’s done by a few colleagues out of Chicago and Baltimore. And it’s really trying to unpack the relationship between weather-related phenomenon like higher temperatures, and the extent to which if you are really controlling for a lot of other factors, do we see an uptick in crime that’s happening? There’s some anecdotal evidence that would suggest that judges move forward on more intense sentences during higher weather—I mean, hotter climates, or hotter temperatures. (37:34) There’s anecdotal evidence that would suggest that crime, actually, greater levels of assault, I think, as a particular measure that they were using, occur as a result of temperatures going up. Our conditions, our environmental conditions, really drive, this is a whole field of social and environmental determinants of health. And we know that there is a relationship between our behavioral response and the things that we experience around us. And so that'’ really where that piece is coming from. Audience member 2 (38:16): Thank you for such an inspirational speech, talk. But I’m curious about what you just said, when we have so many developments, developers building everywhere in the United States, but particularly, they’ve been given extra tax advantages to build up. What happens to these neighborhoods with two-family homes or that have gardens around when they get kind of inundated with these buildings that are 9, 10, 20 stories high? What happens to our quality of life and air quality, traffic, etcetera? And how do you mitigate that? Because you said if a building is higher, we can figure out a way to make it not cause damage to our climate or heat. How does that work? Thank you. Dr. Vivek Shandas (39:08): Yeah. Yeah, that’s good. This is at the core of a lot of the work that we’re involved with right now. So the question is about, and if I reinterpret it in my own words, how do we think about the development process of new buildings going in, for example, and its relationship to climate or temperatures in many ways? And how do we actually get ahead of that? If I understood the question, right. So just two quick thoughts about that. And one, and this is like volumes of work that needs to happen. But two quick thoughts about that. The first is that when developers, and I’m trying to work with developers a lot more, and trying to suspend judgment and trying to really get into their minds and think about how it’s working. (39:54) Developers often are thinking 10, 15, 20 years out in terms of a development of a particular place. It’s not happening, you know, six months ahead, it’s long time frames. So the first thing I feel like we need to be doing if we are the kind of tree-greening community as a collective, we need to be thinking in those longer-term time frames. So that’s the first thought is, being reactive to a development, is fine, it can work. But often it gets crushed very quickly. I’ve been, I have the fortune, I just stepped down from 10 years of being the chair of the city of Portland’s Urban Forestry Commission, which is an advisory group to the city. And the kinds of things that I see often happening is that a developer will move forward on a development and then try to put some popsicle trees, as I like to call them, little trees just to kind of appease, and that doesn’t quite work. So when we start talking about the pedestrian design guidelines, mundane but so important, when we start talking about street redesign guidelines, they have to often be updated, we collectively have to have a role to play in those processes. (41:09) So we have to get into the process where guidelines are being set up, because developers are doing everything by, you know, to the tee, above-board, it’s all legal. But that lends itself to, Whoa, these codes did not prioritize, did not value, the things that might be important to value in this neighborhood. So that’s the long-term perspective. The shorter-term perspective is that we know that we can design buildings, and neighborhoods and city blocks, where the kind of configuration, the materials we use, the kind of structures and where they’re located—I was just hearing from Adrian about, was it the Brooklyn Bridge waterfront where there was a lot of buildings that were being proposed? When you put buildings next to a waterway, that immediately blocks the wind from being able to cool neighborhoods adjacent to that waterway, right? And so we're thinking about where these particular kinds of buildings are going, what kind of materials they would use, what configuration they take. And those shorter-term decisions play a really big role in terms of how we can keep cities cool, while also finding ways to green them. Audience member 2 (42:21): There’s no control over it. We even, I sit on a community board, and we don’t have that much to say, it’s very much a deal already done. Dr. Vivek Shandas (42:29): That’s the heart—yeah. That’s like, right, right. Audience member 2 (42:36): And it’s all because there’s money to be made. And that’s the bottom line. Dr. Vivek Shandas (42:41): Yeah, yeah. Very much so, yeah. Adrian, you want to, quick response? Adrian Benepe (42:48): I would say, don’t get me started. We could talk forever about big buildings and the impacts they have. Can you talk a bit about trees and their ecosystem services, all the benefits they have? And what we’re learning a lot about now between, you know, it’s important to plant a small young tree, but the importance of the big old trees and preserving them. Dr. Vivek Shandas (43:10): Yeah, you know, so I want to try to tie these two together real quick—what feels like a very boring topic of preservation of existing tree canopy. The reason I call it boring is because you don’t find a lot of preservation frameworks or ideas about how to keep a tree in its place. We find often, take it out, put another tree in. The replacement model is often what we see in cities. The tricky part about that is when you take out, as you might imagine, take out a big tree, put in a small one, the loss of shade, the loss of absorbing rainwater, the cooling effect it has, the biodiversity for birds and for insects and for earth to actually have a little bit of its own manifestation in that neighborhood in what I call charismatic megaflora. Like, that’s gone. And so part of the challenge that we have with the replacement model is we don’t really have good frameworks for being able to say, what are the mechanisms for being able to keep a tree in its place? (44:17) If a private landowner wants to take that tree down, they can take it down legally, no problem. So what are the incentives? What are the mechanisms by which a municipal agency dare I say it, a garden, could support neighborhoods for preserving existing charismatic megaflora? I know of one program where I’ve really tried to champion this, called the Heritage Tree Program. It’s around in many different places. We created an online interactive tool, where we were able to identify all the trees that were above 55 feet tall on private property, and that were likely to be taken down because the code would say that a tree that's 10 feet or closer to a structure could be taken down without any replacement, right? (45:01) So we are trying to identify those trees and call those trees heritage trees, because they then get documented in county property records in perpetuity. And so those are mechanisms. And we’re actually working in the LA project that I mentioned, to try to figure out, in LA, how do you keep the existing canopy in place? And that’s one of the next big, I feel, agendas, planting million trees, great. Do it, do it, do it. Keeping the existing canopy and cities—woof. Like, let’s get in front of that as soon as we can. Yeah. Audience member 3 (45:40): So. Hi. All right, I’m gonna try to formulate the question or following up on what you just posed. So, I live in a neighborhood in Brooklyn, I guess it probably would have been in like an A or B, where today, there still are a lot of old trees, and you can see them—I’m sorry, it's just like, I'm a little nervous about it. So I love these trees. I mean, I can only imagine how old these trees are. And I literally lose my breath every time I walk into a park, and it happened twice this week, where I saw two more older trees cut down, and it's almost like I’m having a mourning of these older trees. Because even though there had been younger trees just planted, and I’m thinking, Well, you know, if I live that long, it’s still gonna take 30, 40, 50 years before those trees reach any type of maturity. (46:49) So I think maybe two questions—it seems that money is a driver of behavior. So one question, I’m going to see if I can, like, tie this back together in terms of an incentive, especially for property owners, to keep the work of maintaining, and maybe it’s easy enough for me because I don’t own a home. However, I know that I benefit from it. So if I can stay on track, is there any type of, of not incentive—or data, where if you look at the same street, one side of the street, the trees have been cut down, the other side of the street, they have the older tree networks. Is there any data showing the advantages and using that as incentive for homeowners or like educating homeowners or communities to keep the older tree structure, instead of replanting the younger trees that’s going to take beyond our lifetime to reap benefits from it? Dr. Vivek Shandas (47:57): Yeah, great. So I was kind of blown away at a study that came out of Toronto. Canadians did it again, they’re so, so ahead of what’s happening in the U.S. in terms of this in so many ways. But nevertheless, we’re catching up, and we’re gonna be there. But there’s a study came out that showed, you know, 10 street trees, increases life expectancy by 10 to 11 years, right. There’s evidence now, a lot more epidemiological evidence that public health has started to see trees. And this was a moment I]ve been waiting for a long time. (48:36) Ten years ago, when I got some early federal funding to do a project called Healthy Trees, Healthy People. People were like, hmm, I don't know, public health folks aren’t interested. Now, the public health world is really getting on board with this. And it’s a community that I think we really depend on. Maternal and child health folks getting interested in this, folks who are really looking at older adults and their ability to stay cognitively, you know, connected to their families, like that is evidence. So the one part I'll say about it is, this is about, from a data point of view, since you use the word, it’s about granularity of information. It turns out getting, New York City has this, but it turns out getting a good data set of tree quality, of size of tree, height of tree, species diversity of tree—those inventories are just now being created. I wish they had been created before. But they’re just now starting, there’s new tools coming online to be able to create these inventories of existing trees, having community groups go out with arborists, and documenting these tree types. (49:38) And so with that type of data, we're going to be able to connect more to public health information and start teasing out those individual associations a lot more effectively. But this field is still arguably relatively young because most of the work is done with satellites that take pictures of you know, one kilometer resolution of a place as opposed to what you’re talking about, a street. And so the more we get that kind of information, I think this field is just really going to kind of start moving, but it’s early. We have stuff, but it’s still relatively early. I wish I had something better for you. You know, we’ve been busy trying to generate it. It’s just hard to kind of get to that level of granularity. Nina Browne (50:17): Unfortunately, on that note, we are out of time. I want to give another round of applause to Dr. Shandas. Register on arrival to secure a spot in the morning and afternoon programs of your choosing. Arrive early to get your first choices, space permitting. Due to limited availability, you must be present to receive a workshop ticket at registration. Workshops repeat at 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. There is a different talk in the morning and the afternoon. ASL interpretation will be available for all talks. Emily Nobel Maxwell, The Nature Conservancy

Dr. Vivek Shandas, Professor of Climate Adaptation, Portland State University

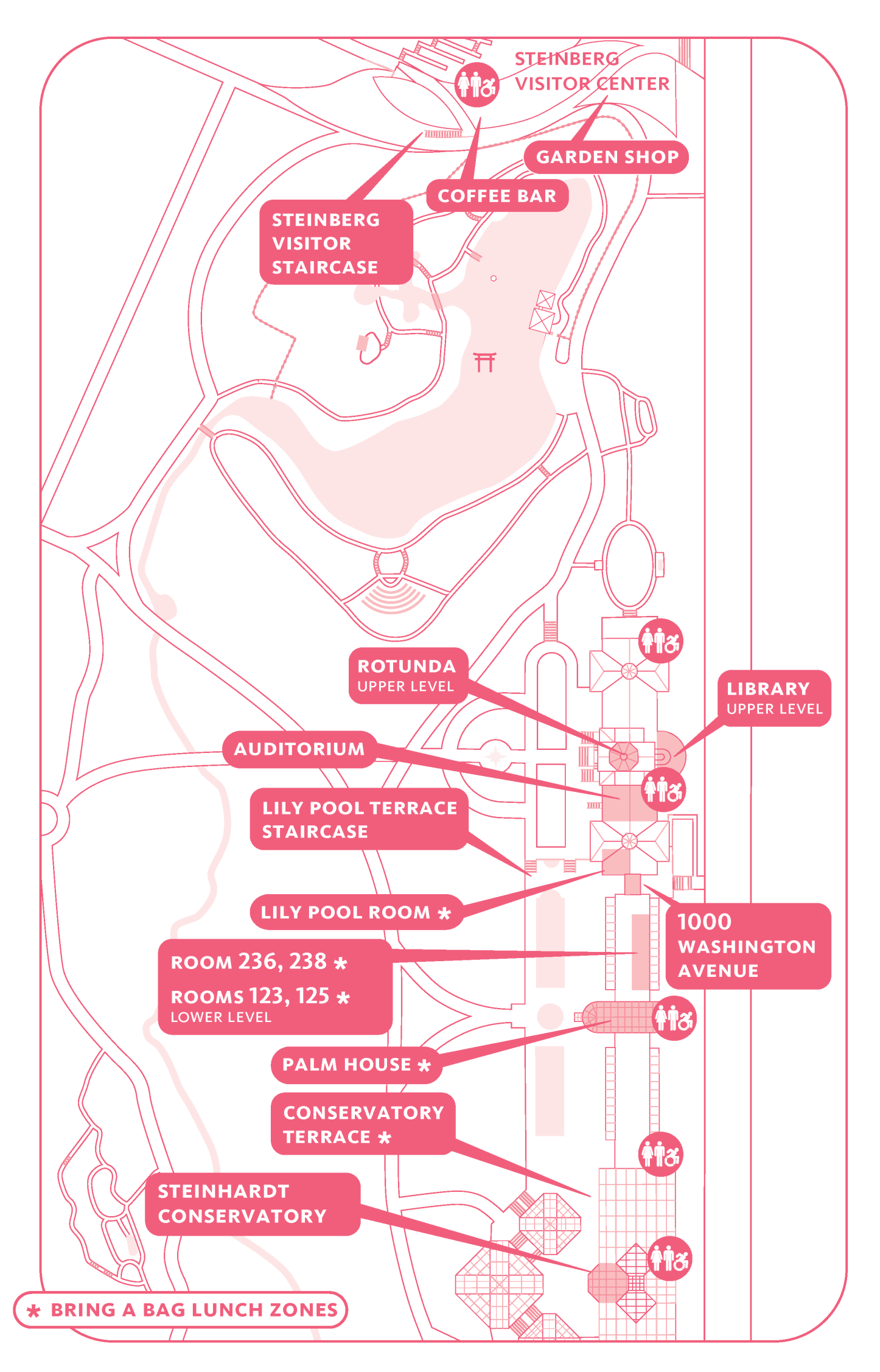

Rowan Blaik, Vice President of Horticulture, Brooklyn Botanic Garden Each workshop runs twice, 11 a.m.–12 p.m. & 3–4 p.m. Lily Pool Room Classroom 123 Classroom 236 Classroom 238 Classroom 125 Join an indoor or outdoor tour with one of our Garden Guides. Garden Guide Jennifer Napoli Garden Guide Katherine Patton Garden Guide Kathryn Hodges Garden Guide Kit Schneider Click or tap below for full-size map. Morning Workshops, Talks & Tours: You may choose one morning and one afternoon workshop, space permitting. See descriptions above. Look for signage in classrooms and the Palm House and on the Conservatory Terrace for areas to sit, eat your lunch, and chat with fellow attendees. Snacks and lunches are also available for purchase in the Palm House. Wilbur A. Levin Keynote Address

Tapping The Power Of Trees: How The Urban Forest Will Save Cities

Wilbur A. Levin Keynote Address

Deeply Rooted: Traditional Knowledge, Equity, and a New Era in Urban Forestry

Dr. Vivek Shandas, Professor of Climate Adaptation, Portland State University

Workshops, Talks & Tours

Auditorium Talks

Speak for the Trees: 30x35

What is the state of the urban forest in New York City? How can community groups and property owners work with government to expand our local urban forest for the benefit of all? Achieving at least 30% tree canopy cover in NYC by 2035 means increasing equity, building community, adapting to extreme weather, and reducing temperatures in the most heat vulnerable neighborhoods. Learn about the NYC Urban Forest Agenda and how you can get involved.

Deeply Rooted: Traditional Knowledge, Equity, and a New Era in Urban Forestry

In the Wilbur A. Levin Keynote Address, Shandas addresses the question, Can urban greening projects address historic injustices, respond to community aspirations, and draw on traditional ecological knowledge?

Protecting the Health of the Urban Forest

One frequent visitor question is: How does BBG care for and protect its trees? Hear from a plant and tree expert whose work is dedicated to monitoring and guarding the Garden’s arboreal treasures. Learn lessons you can take back to the treasured trees in your life.

Classroom Workshops

Bees, Trees, and Beans: Stories of Vanilla’s Ecological Interdependence

Maya Marie S., Deep Routes

Vanilla has long been prized for its floral, sweet yet smoky smell and taste. But do you know about vanilla’s origins and the complex, interdependent relationships that make its existence possible? Learn vanilla’s botanical wonders while making vanilla extract and reflecting on our relationship with this beloved spice.

Beginning With a Seed

Joanne D’Auria, HortAbility

A great workshop for beginning gardeners! Learn the basics of seed types and life cycles. How do gardeners coax the most out of seeds and how does seed-starting compare to other forms of propagation? You’ll start some seeds for your garden or windowsill.Street Tree Stewardship—Lessons from the Greenest Block

Perri Edwards, Althea Joseph, Jaime Joyeaux, and Lauren Wilson, Preserving Lincoln’s Abundant Natural Treasures (P.L.A.N.T.s)

The gardeners of P.L.A.N.T.s—two-time winners of BBG’s Greenest Block in Brooklyn contest—will share their insights and expertise on the preservation our tree neighbors need. Learn street tree care basics and how to use a love of trees to organize, motivate, and inspire connections on your block. What Does Racial Equity Have to Do with Street Trees?

Brandon Otis and Suzy Myers Jackson, Brooklyn Urban Gardeners

Caring for trees can be a liberating act of service and learning. The legacy of redlining means less tree canopy and more pavement in historically Black neighborhoods, which has negative financial, environmental, and health impacts for residents. Get inspired to advocate for more trees in your neighborhood and beyond.Worm Composting at Home

Teddy Tedesco, NYC Compost Project Hosted by BBG

Compost happens—even in your tiny apartment! Learn how to harness the power of red worms to convert your kitchen scraps into black gold, no matter where you live. Special Tours

Trees of Little Caribbean in the Conservatory

Visit the Entry House, Aquatic House, and Tropical Pavilion and learn more about native Caribbean trees like guava and allspice as well as plants from across the globe that have thrived there since colonization. This tour is 30 minutes.

Native Trees on the Garden Grounds

What makes a tree “native” to Brooklyn? Why are native trees, and the relationships all around them, so special?

Learn more while enjoying some early-spring surprises. Bonsai Museum

Inside a small form, bonsai embody a tree’s vast message of compassion and curiosity for nature. Explore Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s world-class Bonsai Collection, one of the largest on display outside Japan. This tour is 30 minutes.

In Your Own Backyard? Tour the Woodland Garden and Maple Grove

Two of BBG’s newest additions, Maple Grove and the Elizabeth Scholtz Woodland Garden are delightful and fully accessible outdoor classrooms full of trees and inspiration for urban gardeners looking to improve their own corner of Brooklyn. Site Map

Schedule

Register the day of the event to secure space for workshops and the keynote address.

Rotunda Activities

Auditorium

“Deeply Rooted: Traditional Knowledge, Equity, and a New Era in Urban Forestry” presented by Dr. Vivek Shandas, professor of climate adaptation, Portland State University

Questions? Contact [email protected] or call 718-623-7250.

Accommodation can be made for visitors in wheelchairs or with limited mobility. If you need additional accessibility accommodation, please contact us at [email protected] by February 21.

Support

Brooklyn Botanic Garden gratefully acknowledges support for its Community Greening programs from Brooklyn Community Foundation, the Family of Wilbur A. Levin, National Grid, NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, the NYS Assembly and NYS Senate, NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, the NYC Department of Sanitation, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, and the NYC Council.

Leadership Support, Community Greening Programs

Major Sponsor, Community Greening Programs